By Victor S. Sierpina, MD

By Victor S. Sierpina, MD

“The beginning is always today.” –Mary Wollstonecraft

During some unexpected free time, I took an online course from the University of Arizona’s Andrew Weil Center for Integrative Medicine. Go to https://integrativemedicine.arizona.edu/ for a large array of online materials and course in integrative medicine. It is a rich, well validated, and dependable resource for the entire spectrum of integrative medicine.

In my case, I decided to enroll in their Integrative Pain management series. It starts with some foundational concepts, some of which I’ll describe here. It then expands to management of pain through diet, mind-body therapies including guided imagery, hypnosis, mindfulness, meditation. Other options include use of supplements such as fish oil, Vitamin D, turmeric, B vitamins, cannabinoids, alternative systems of care like acupuncture, body work such as osteopathic and chiropractic treatments, massage, energy medicine, and much more. There is an excellent section in the course I took on withdrawing patients from opioids safely.

Consider enrolling in this or other Integrative Medicine courses if you or your team treat difficult to manage chronic pain patients, or wish to use integrative medicine for areas like chronic back pain, headaches, rheumatological pain, fibromyalgia, pain in children, and more.

So what is pain?

“Ouch!” you bang your finger with a hammer or touch a hot stove. You immediately feel signals your body and brain recognize as pain. This is an acute, rapid process mediated through several steps in your nervous systems. Specialized cells called nociceptors, think live wires, are activated at the site of injury as certain chemicals called prostaglandins flood the area of tissue injury. These wires connect to several kinds of nerve fibers, fast and slow that take the pain signal up your spinal column to the brain. It’s like a pain train going along a track.

Like grand central station is a brain structure called the thalamus that distributes the pain signal to different areas that note the location, intensity, activating motor areas as well as emotional response and memory.

Pain is a protective mechanism and serves in our survival. A genetic syndrome that prevents pain awareness results in early death. Damage to nerve fibers such as in diabetes or leprosy results in lack of awareness of tissue damage and resultant ulcerations, infections, and deformities.

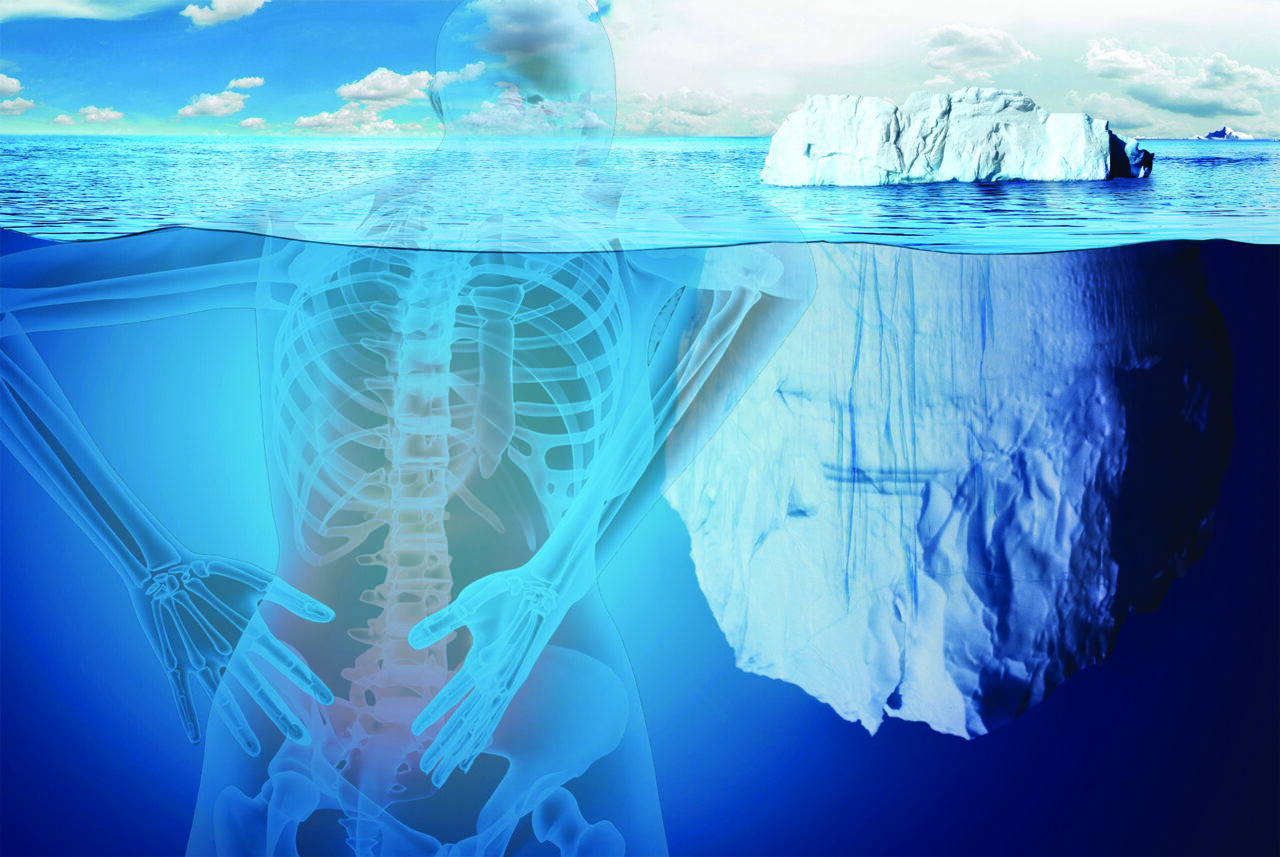

However, acute pain can become chronic. This is closely associated with our current epidemic of opioid overuse, abuse, overdoses, and deaths. In chronic pain, the body develops heightened responses to pain. These are called peripheral and central sensitization syndromes. The peripheral tissue continues to send a barrage of signals to the brain long after the acute injury is gone. The brain in turn, overwhelmed by the constant signals, dampens the receptors and pathways of pain signal processing, at least for awhile. Eventually cells that inhibit painful stimuli are crowded out and replaced by cells and parts of the brain not usually associated with pain. This signaling causes anatomical changes via neuroplasticity imbedding hypersensitivity to pain in multiple brain areas. In other words, the brain is in pain.

Ever higher and constant need for drugs like opiates is a consequence. Another phenomena may also occur, opiate hyperalgesia, in which not only do the opiates no longer block pain as the brain fights back with its own nociceptors causing additional hypersensitivity. More medication doesn’t help and a vicious cycle ensues.

Studies of post-surgical patients found some predictors of who would likely move from the acute pain of surgical recovery to chronic pain. These included a variety of psychological and physical factors: chronic pain is more common in women, genetics and family history, obesity, prior post-traumatic stress, depression, insomnia, poorly controlled blood sugar, poor protein nutritional status, anemia, deficient iron or low vitamins A , B12, and D. Supplementing inadequate nutritional status can be preventive to keeping acute post-surgical pain from entering a chronic phase.

Some years ago, a patient gave me a series of tapes that he used to boost his physical, emotional, and immunological readiness for surgery. Such preparation can be useful through certain pre- and post-surgical exercises available online at sites such as: https://www.preparingforyoursurgery.com/

While not all chronic pain can be avoided, be aware of not only its impact on quality of life, disability, and accompanying emotional turmoil, but also the high rates of addiction, substance abuse and misuse. Prescribers are increasingly aware of the hazards and pharmacies have started limiting initial amounts of controlled substances for acute problems to reduce risk of long-term dependence.